Essay: Through the Wilderness with Sam Grant (Complete) (Part 1 of 9)

He took upon his everyman’s shoulders ultimate responsibility for saving our Nation and redeeming its promise of liberty. How will we honor his legacy?

Introduction

Culpeper should be a national shrine.

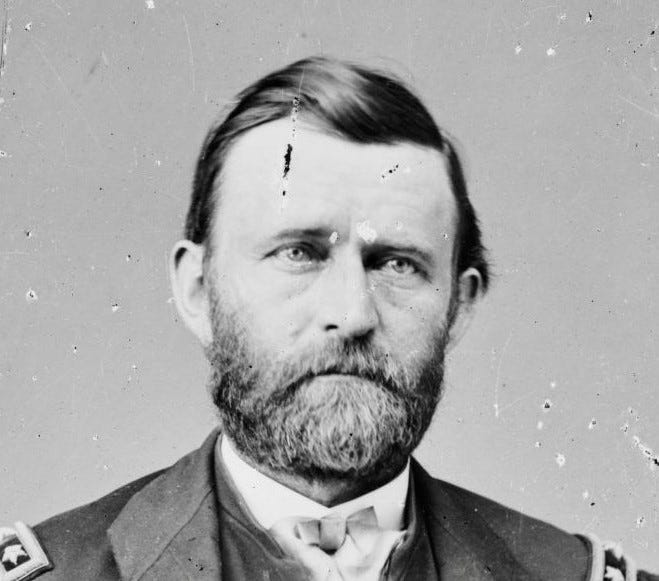

From March to May 1864, Ulysses S. Grant made his headquarters in Culpeper, Virginia. It was from there he planned and launched the ferocious Overland Campaign that ended the standoff along the Rapidan River and turned the momentum toward reelection for Abraham Lincoln and final military victory for Union forces in the Civil War.

If not for the train of events begun in Culpeper and driven through the Battle of the Wilderness by Grant’s steadfast leadership, slavery would have remained entrenched in the South for decades to come. Grant himself wouldn’t have succeeded to the Presidency in 1868, and America never could have pushed forward the nationwide moral battle for Reconstruction and civil rights that U.S. Grant personally championed from 1865 until 1877—a moral battle that still provides, after more than a century of stifling suppression, the lodestar for our Nation’s continuing collective racial reconstitution.

We in today’s America need to reanimate this history, reinvigorate the spirit of Grant, and reaffirm the moral convictions supporting the great civil rights mandates approved by Congress under its power to enforce our Constitution’s Civil War Amendments.

Part 1

After his bold and unorthodox campaign to take Vicksburg and his brilliant resupply and defense of Chattanooga against dire odds, U.S. Grant emerged from the sweating West into the clear center of President Lincoln’s vision as the singular man who could win the War in the field.

On March 2, 1864, Lincoln made Grant general in chief of all Union forces and asked the Senate to confirm him (as only the second man in history after George Washington) to the preeminent rank of Lieutenant General of the Army, a commission he received on March 9. (Winfield Scott had also been made Lieutenant General, but by brevet, or honorary, promotion.)

The Union had endured two and a half agonizing years of fitful advances and disheartening reverses on the battlefields of Virginia and Maryland, and Lincoln felt the crushing weight of these military setbacks. He had so often interjected himself as tabletop commander, repeatedly adjusting and countermanding the war plans of his generals, and he had suffered over and over again such penetrating disappointment and frustration when one after another of his chosen commanders, battered and bloodied by Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, gave up pursuit, failed to carry forward the fight, and retreated backwards to reorganize and reprovision north of the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers, their military resolve, emotional confidence, and leadership capacity utterly broken and embarrassed.

Now, in March 1864, with his elevation of Grant, Lincoln finally committed to deliver himself of the military burden. He ceded to his new general in chief complete discretion for prosecuting the War to its conclusion—and thus Grant was entrusted to act as the final helmsman for the entire fate of the Nation.

Following brief consultations with Lincoln at the White House, Grant immediately traveled to Brandy Station in the vicinity of Culpeper, where he inspected the Army of the Potomac, more than 100,000 Federal soldiers massed in the surrounding fields, and met with its commanding general, George Meade, on March 10. He then rushed by train back to the West to huddle with his most accomplished and trusted field general, William Tecumseh Sherman, in a series of meetings on March 18-21 in Nashville, Louisville, and Cincinnati hotel rooms.

It was in those hotel sessions with Sherman that Grant sketched the general outlines of his national war strategy, the first overarching coordinated military strategy actually implemented by the Union during the War:

Grant would command from the field in Virginia, accompanying Meade’s and General Ambrose Burnside’s forces to battle Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia by a relentless push southward from the Rapidan toward the Rebel capital of Richmond.

Meanwhile, Sherman would take over from Grant as commander of the Division of the Mississippi and would lead a combined force drawn from the Armies of the Cumberland, the Tennessee, and the Ohio (the Union Army named most of its largest commands after rivers) in a concentrated campaign through Georgia from Chattanooga, engaging Rebel General Joe Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, to take Atlanta and cut the Confederacy’s railroad arteries in Georgia—a campaign that eventually included Sherman’s march to the sea and his swing northward through the Carolinas.

In addition, Grant would dispatch troops to clear the Shenandoah Valley, launch a force up the James River to try to cut off Richmond from the south, and order a campaign into Alabama—three collateral maneuvers that, in the event, failed to achieve their assigned goals but that helped the overall effort by occupying significant Rebel forces while Grant and Sherman’s main campaigns moved forward.

Returning to Culpeper on March 26, Grant set up his Virginia headquarters in a stately Federal-style brick mansion, the John Barbour house, which sat sideways at 120 West Davis Street, next to the Culpeper County Courthouse. And within the Barbour house, he and his staff prepared the detailed orders that put the wheels of the grand victory strategy in motion.

John Strode Barbour, Jr., president of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, had abandoned his home and left town to serve the cause of the Rebellion. Most of the buildings in Culpeper, in fact, had been vacated by their owners as the town’s citizens fled south to the protection of Lee’s army, and the Union command staff had occupied Culpeper as a base ever since General Meade aborted his Mine Run Campaign at the beginning of the previous December.

In the predawn darkness of Wednesday morning, May 4, 1864, U.S. “Sam” Grant (so nicknamed by his West Point mates after “Uncle Sam”) began the Overland Campaign by marching two corps of the Army of the Potomac from their camps around Culpeper down the Germanna Road toward Chancellorsville. Per Grant’s coordinated orders, that same morning, south of Chattanooga, Sherman and his forces moved into Georgia.

Grant himself rode out from the Barbour house on his large bay, Cincinnati, and from the elevation of Fort Germanna, the site of a historic colonial settlement of German immigrants, he watched the endless lines of Union infantry crossing Germanna Ford on two pontoon bridges (floating chains of boat shells, overtopped by wooden planking). A third corps, under General Hancock, crossed downstream at Ely’s Ford, and the Army’s supply train of wagons and cattle herds would begin to follow later that day, crossing in between at Culpeper Mine Ford. A fourth corps, commanded by General Burnside, remained in the rear protecting the rail lines to Washington and was to trail the Army of the Potomac over the Germanna Ford a day or two later.

Grant’s objective in crossing the Rapidan was to engage Lee’s army at the earliest opportunity but on the most advantageous ground possible, not by moving directly south from Culpeper along the Orange & Alexandria to meet Lee head-on but by sidling toward the southeast across Lee’s front and drawing Lee to him. Grant’s hope was to march his forces quickly through the dense woods of the Wilderness and then swing west, bringing a challenge from Lee somewhere in the open fields between Mine Run and Todd’s Tavern.

But alerted by scouts to Grant’s river crossing, Lee lost no time putting his forces in motion to converge on the Army of the Potomac before it could clear the Wilderness. From their bases east of Orange Court House and south of Mine Run, Lee’s troops hustled up the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road toward Wilderness Tavern, and their forward brigade confronted the advance corps of the Army of the Potomac early Thursday morning at a small clearing in the midst of the tangled woods. From there the Battle of the Wilderness exploded over two days, May 5 and 6.

The Wilderness in May 1864 was a wide stretch of second-growth forest, thick with saplings and choked with dense underbrush. The opaque curtain of woods at ground level negated the Union’s numerical advantages in troops and artillery and made the battle experience for rank-and-file soldiers a high-tension chaotic horror.

The troops groped through tangled brush and vines and furiously dug and re-dug protective trenches as the lines of battle surged and shifted. Infantry and artillery fired blindly through the leafy thicket, increasing the instances of friendly fire casualties, and much of the fighting occurred in close-range and hand-to-hand combat through sudden convulsive encounters.

Most horrible of all, the exploding shells ignited brushfires that soon developed into fast-moving blazes. Many of the wounded soldiers lying bloodied and in pain on the forest floor were engulfed by the fire and burned to death, and their terrifying cries of anguish rang out across the battle zone all night long and through the remainder of the battle.

May 6, the second day of fighting, was a close thing for the Union forces. The south (or left) side of the Union line under Hancock made an early advance westward down the Plank Road, but that advance was repulsed when the forces of Confederate General Longstreet arrived to bolster Lee, and the left side of the Union line was soon broken and turned. Late in the day, the right side up along the Germanna Road was also turned.

Through much of the afternoon at his headquarters tent just off the Orange Turnpike near Wilderness Tavern, Grant received dire reports of Rebel advances and impending collapses of the Union lines, including a frantic prediction that Lee’s forces were about to overrun the Germanna Road, exposing Grant’s supply trains to the northeast of the Wilderness and potentially cutting off his avenues of retreat. At one point, Confederate shells fell close to Grant’s tent, and he was urged to move his headquarters back to the rear.

He didn’t budge. He and Meade stayed steady and directed that the lines be held and reinforced. Burnside’s corps finally arrived in mid-afternoon and strengthened the Union’s center, and the fighting ended at nightfall in a ragged clenching standoff, overhung with smoke from the burning woods and the stench of burning flesh. Grant’s staff reported that on May 6 he smoked more of his strong cigars—at least 20—than on any other day during the War, and he whittled away at so many sticks that he put holes in his gloves.

Although the battle closed in a rough stalemate, the Federal forces had received a major bloodying, and the level of destruction was staggering. In just those first two days of clashing horror since Grant had crossed the Rapidan, the Union had lost 17,500 men.

Think about the weight of that number—Grant must have received preliminary estimates by the battle’s end, and the fullness of the losses must have been burning in his mind on the evening of the 6th. (Grant initially thought Confederate losses were even larger; Lee’s army had, in fact, suffered around 11,000 casualties, a similar proportion of his forces at hand (about 18%), though Lee had far fewer available reinforcements than Grant.)

The almost unfaceable enormity of what the Overland Campaign would require of the Union Army, in blood and destruction of tens of thousands of lives, and directly of Grant and his subordinate commanders, in terms of the most intense unrelenting concentration of will and steeled nerves, was now truly present for him and obvious.

When dusk finally came that second day of the Wilderness and the fighting had ended for the night, Grant was overcome with grief and emotion. His closest staff members accompanied him into his tent, and for the only time they could ever remember, they saw him collapse, weeping, on his cot, raw and immobilized with emotional anguish. The lonely anguish of his personal Gethsemane spilled out and gradually gave way to weariness, and within about an hour, he was sleeping.

Emerging from his tent later that night, he sat calmly and quietly at the campfire. History, the entire future course of the Nation, hung suspended in the thick acrid air, during a night that tested Grant’s steadiness and resolve even more than the night he endured after the chaos and setbacks of the first day of fighting at Shiloh.

The next morning, Saturday, May 7, after Union probing confirmed that Lee had drawn his lines back with no immediate intention of pressing the battle, Grant gave orders for the Army of the Potomac to pull out eastward, starting with the artillery battalions in the late afternoon, followed after dark the night of May 7-8 by an orderly movement of the many infantry brigades.

Because of the unyielding fierceness of Lee’s springing attacks in the Wilderness and the horrendous losses suffered so abruptly there by the Federal forces, most of the soldiers in both the Confederate and Union ranks assumed (the Rebels with prideful joy and contempt and the Federals with habitual resignation and defeatism) that Grant was executing a retreat.

They expected the Army of the Potomac to fall back through Chancellorsville and then retire north across the Rapidan, where it would return to bivouac and nurse its wounds—perhaps to reorganize under yet another new commander. Just as Meade had done after the fumble of Mine Run, Joe Hooker after the embarrassing disaster of Chancellorsville, Burnside after the bloody futile bashing of Fredericksburg, and George McClellan after his gallant Peninsula Campaign had stalled and lost its heart in the marshes east of Richmond.

Grant’s plan for the Overland Campaign, assiduously worked out in the comfort of the Barbour house, was to keep pushing his forces toward Richmond, outflanking Lee to the south and east after each engagement, receiving supplies via the inlets of the Potomac, Rappahannock, and York Rivers, and compelling Lee to maneuver his own army farther south to stay between Grant and the Confederate capital. The strategy was to grind Lee down in a series of clashes, ultimately forcing the capitulation of the Army of Northern Virginia and the surrender of Richmond.

But, as the great Mike Tyson has so eloquently reminded us, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” The Battle of the Wilderness—the loss of 17,500 Union soldiers in two days—was a powerful punch in the mouth, right at the opening bell of the campaign. Every previous commander of the Army of the Potomac had lost his confidence and fighting drive when confronted with just such a painful shock. Those examples show the superhuman pressure and onus of responsibility that military commanders must internalize when they experience so much bloodshed and loss of life suffered under their orders.

History (the reality of history as experienced in pain by those living through it) had now called the question for Sam Grant.

Grant stuck to his plan. The orders he gave Meade on the morning of May 7 were not to retreat but to move the Army east toward the intersections with the Brock Road and then to turn south down the Brock Road and march the Army as quickly as possible through Todd’s Tavern toward Spotsylvania Court House, where Grant hoped to gain a strong position for the next confrontation with Lee. To reinforce his move southward, Grant ordered the pontoon bridges taken up from Germanna Ford and the establishment of supply terminals on the Potomac waterside.

When the Union troops realized in the early morning of May 8 that Grant was leading them onward toward Richmond, not back to bivouac, they broke into cheers—even though they knew this direction consigned them to the unavoidable horror of more battles like the Wilderness and the certainty of death for so many of them.

The cheers erupted again and again down the columns and caps flew in the air that morning as Grant and Meade on horseback passed by the troops as they marched southward along the dirt track of the Brock Road—the very same track Stonewall Jackson had galloped in the opposite direction one year and six days before, when he orchestrated the devastating flanking attack on the rear of Hooker’s forces in the Battle of Chancellorsville, just before receiving his fatal wound from friendly fire.